Besides a handful of Asian and European countries which remain to have strict enforcement of Covid restrictions, Australia has been one of the most cautious countries in the world when it comes to lockdowns. It wasn’t until late 2021, which until then had essentially seen constant lockdowns in one region or another, that lockdowns began to cease.

Heading into 2022, with a realisation that the country had surpassed its vaccine targets and that Omicron was milder than Delta, it was now time to “live with this virus”. Cautious policy and a willingness to protect lives over the economy wasn’t the only reason for the lockdowns, of course, but also Australia’s strong financial position heading into it – with relatively low debt to GDP and strong reserves.

For some more perspective of the extent of Australian lockdowns, the UK had phased out lockdowns since the 8th March 2021. Although some of the rules had fluctuated since then, gyms, cafe’s and businesses remained fully open since – which is coming up to a year ago now. However, since the 8th of March in Australia, we saw Sydney impose limits on visitors to the home, Victoria entering its fourth, fifth, and eventually, sixth lockdown, Sydney announced lockdown measures and restricted it to be 5km from their home.

Not only are these lockdowns recently ending, but the borders have just been announced to fully open up to travel too for fully vaccinated travellers – with Australia having a fairly big tourism industry. Finally, the Australian economy prediction for 2022 is looking like it’s getting back to its usual self despite cases rising.

The health of Australia’s economy

In late 2020, when the pandemic was peaking to its worst stage – prior to sufficient knowledge, healthcare, or vaccines in its response – the Australian economy entered its first recession in 30 years. This alone tells the story of just how much Covid-19 and subsequent lockdowns impacted the economy in 2020, with otherwise buying customers locked in their homes, only to be allowed to go to the grocery store or for a walk.

GDP shrank by 7% in the second quarter of 2020, its biggest fall since 1959. Given that it saw a fall of 0.3% in the first quarter, Australia had entered its first recession in decades – a fact that had been separating Australia’s strength from other western economies, which were deeply damaged by both the dot com bubble and the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis.

In response to this recession, we saw some instant rebound growth – with a 3.4%, 3.2%, 1.9%, and 0.8% quarterly growth following the recession – until an eventual -1.9% contraction in the economy 5 quarters after the recession. This somewhat represented the cyclical nature of the virus, with the virus spreading more in winter, along with a cyclical nature to the lockdown restrictions.

The upside of this cyclical nature is that it soon became apparent, and therefore businesses could have some level of foresight into this for cash flow planning – though having the foresight isn’t necessarily enough.

However, before looking at SME’s cash flow, it’s important to point out the supply chain disruptions. Australia is already a remote country, far away from the EU – which is one of its largest trading partners. Travel bans, workforce disruptions, and a deep chip shortage led to supply chain issues in Australia, with tech companies struggling to build their products and costs on the whole rising.

Like with most economies, this led to cost-push inflation (not demand-pull), which is the worst kind. Although this wasn’t a huge issue during the peak of Covid in 2020, in part because demand had also reduced (thus creating a fairly stagnant equilibrium), as consumer confidence rose, the supply issues became even more apparent, leading to inflation rates of nearly 4%.

Whilst this sounds bad, being almost double the 2% target rate, it actually fared a lot better than the EU and US inflation, with the latter climbing steadily from near-zero in mid-2020 to 7.5%. In other words, the US Federal Reserve has reacted to this inflation by hiking rates up, whilst the Reserve Bank of Australia has remained stoic – even if the inflation rise was much greater than the RBA forecast.

At the end of 2021, the unemployment rate was 4.2%, which is fairly good compared to its peers, but the low unemployment doesn’t seem to have translated into wage growth (around 2.2% in September 2021), which could be a concern given the current inflation rate. Wage growth is currently 5% in the US and 4% in the UK, in comparison. However, worker shortages due to Brexit are playing a role here. On the flip side, it can be argued that this lower wage increase is at least not exacerbating inflation.

SMEs struggle and loan guarantees resume

Small to medium-sized enterprises account for 99.8% of all Australian businesses – a very high proportion. SMEs also account for employing 7.6 million workers in Australia (around 68% of the employment in the private sector), so their health also impacts everyday Australians – not just the small business owners.

In fact, whilst Australia used to rely more on the mining boom, SMEs played a central role to the transitioning of a broader economy that now has a growing tech sector. Because of this reliance on SMEs, it meant that a core goal of the Australian government was not to neglect them during the pandemic – not least because SMEs were likely to be the shops and companies that were told to close due to restrictions, along with shifting workers to online.

One scheme brought in by the Australian government was JobKeeper payments, which meant eligible businesses could receive $1,500 per fortnight to cover wage costs. However, when the programme ended in March 2021, it was predicted that thousands of businesses would default in the following months – and many did.

Another programme that was due to end was the SME Recovery Loan Scheme, which helped provide financing support to small businesses. It allowed credit to be cheaper, with the government guaranteeing 80% of the loan amount. This SME Loan Guarantee Scheme was vitally important to the cash flow of small business finance, allowing them to have the capital to adapt to the Covid-19. Not just in paying wages and surviving, but proactively adopting new strategies that were more aligned with e-commerce, remote work, and the drastic changes that the pandemic had on our lives and habits.

Whilst the scheme has been extended now to the end of June, 2022, the government guarantee has dropped to 50%.

It certainly signals a winding down of government grants in Australia, and general financial support, despite the hangover effects that the pandemic has had. Small businesses are still struggling, having larger amounts of debt and supply chain issues remain. Many territory schemes are absent too, like no local schemes in NT or Queensland. Furthermore, we are only a few months from June 2022, when the SME Recovery Loan Scheme ends.

As a result, many small businesses are using a guide like Small Business Loans Australia for extra private financing, and this will be particularly popular come June. The way Australian small businesses seek small business loans is drastically shifting away from banks and onto the web, with online lenders having flexible creditworthiness standards and rapid application approvals – often being within 24 hours, making it ideal for impromptu and last-minute cash injections.

The northern and capital territory governments remain the most generous, though there is still a nationwide winding down of programmes.

The future of Australia’s economy

With restrictions and schemes winding down, we would expect to be optimistic for Australia’s economy throughout the rest of 2022. However, Covid-19 cases can affect consumer confidence (as well as possibly introducing new measures again), and we are seeing a fairly steep increase in cases each day. In late February, there were 18,000 new cases per day. From each day on, cases climbed on 5 consecutive days in a row, reaching 35,855 new daily cases on March 3rd.

As we have seen in the UK, however, Omicron’s presence was rapid, milder than previous strains, and left the UK with high immunity – with cases now falling there. It is expected that the same will occur in Australia.

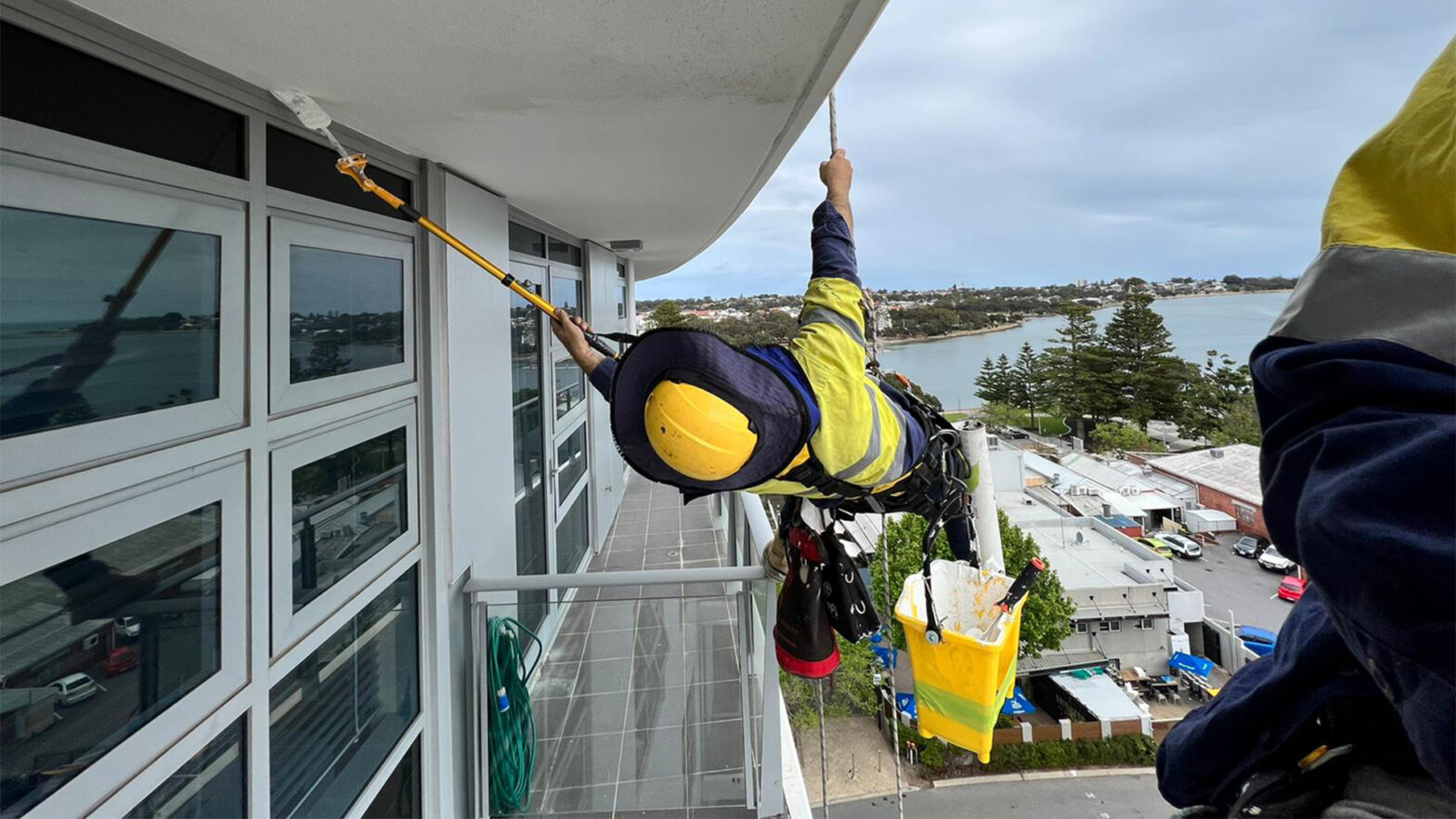

What has more impact than cases, though, is restrictions, and the winding down of them will undoubtedly be a boost to SMEs. After 2+ years of absolutely no profits, the tourism industry is set to reignite, particularly with the high vaccination rates among countries that frequently and historically visit Australia.

Omicron is expected to “drag on economic activity during early 2022” because high cases mean more workers isolating – and worker shortages can also cause wage inflation and CPI inflation. Total hours worked and consumer spending is also looking likely to decline in the short run due to this Omicron spike. So, it’s certainly too early for small businesses to celebrate.

However, most analysts are seeing the light – and a lot of that comes from the anticipation of Omicron cases quickly peaking and declining due to the high vaccination rates and milder symptoms. Around halfway through the year is when the bounceback is forecast, with consumer and business confidence set to rise once again – and hopefully, sustained, presuming there are no new Covid-19 variants.

Broad economic growth is expected to be boosted from July onwards, particularly in part due to the strong labour income growth and strong savings and wealth from Australians.

We can’t ignore the current political situations in Europe, of course, with the recent invasion of Ukraine. The economic impacts of this are less immediate than in Europe, of course, but oil price rises have already been introduced, and business with Russia has become more difficult. Speculation on the military events are too difficult to predict, but Australia is not protected from the economic ripples that could occur.

Inflation is set to level out at a healthy 2-3% from 2023 onwards, whilst disposable income and consumption is set to continue growing. Not only is this good news for Australia in isolation, but it’s even more impressive in relation to their peers who are suffering steep inflation that far outstrips their wage increases.

Some other possible risks for the Australian economy comes from China’s slowing economy, which is likely to reduce demand for some exports, mostly commodities like iron ore, and construction.

Looking back, it is easy to point out the shortcomings of the Australian government along with the struggles of SMEs, but it’s important to see it within the context of its peers. What stands out is Australia’s foresight in its previous economic success over the past few decades. Despite Australia withstanding far more lockdowns than the US, and thus longer pandemic relief programmes, we have seen less of a rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio, signalling that Australia had built up healthy reserves and savings when the times were good.

For comparison, Australia’s debt-to-GDP climbed from 41% in 2018 to 62% in 2021. In the US, these figures were 107% to 133%.